Anja Pastor: Dr. Dirk, é um prazer estar hoje convosco. Obrigado por abrir a nossa série de entrevistas! O primeiro tópico será "A relevância da inflamação".

Em primeiro lugar, como é definida a inflamação?

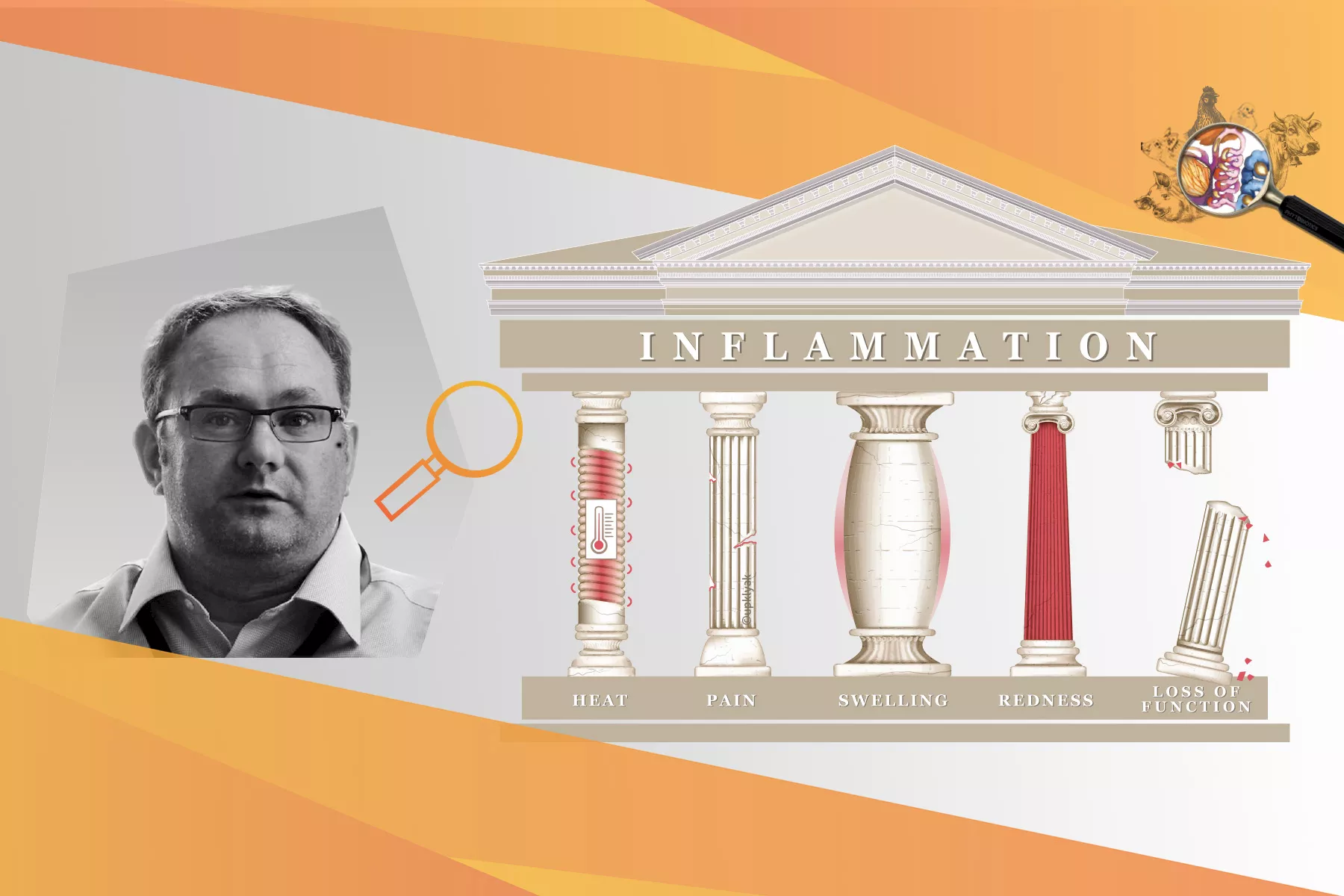

Dr. Dirk Werling: Imagine um corte na sua pele. Irá notar vermelhidão, inchaço, perda de funções, calor e dor. Estes 5 sintomas cardinais são o que realmente define um processo inflamatório agudo. Este princípio é válido para os locais de inflamação em qualquer parte do corpo.

AP: A inflamação é parte do sistema imune inato. Se o sistema imune inato fosse um ser humano, que tipo de trabalho teria?

DW: O sistema imunitário inato seria provavelmente um polícia padrão, sempre em patrulha. Em contraste, o sistema imune adaptativo - produzindo anticorpos - é mais especializado, algumas partes muito especializadas - comparável a uma unidade de polícia especial que lida com terroristas.

AP: Por que a inflamação é tão importante que precisa de uma equipe sempre atenta?

DW: Devemos ter em mente que o sistema imunitário não é um sistema que liga e desliga. O sistema imunitário precisa de ser capaz de reagir rapidamente a qualquer ameaça potencial para proteger o corpo de danos e assim garantir a sobrevivência.

A Inflamação tem 2 funções principais. Alertar o sistema imunitário de que algo está a acontecer num órgão/tecido específico que precisa de ser tratado e colocar todo o corpo num estado de pré-aviso. Desta forma, se os danos não puderem ser contidos nesse local, ainda podemos proteger os restantes órgãos. Isto é independente do local da infecção e a transição de uma reação local para uma reação sistêmica é fluente.

Como resultado, todo o organismo participa em tornar a vida dos agentes patogénicos tão desconfortável quanto possível. Existe, por exemplo, uma mudança de comportamento: se o animal estiver doente, come menos e o uso da energia passa dos açúcares para a gordura. É fornecido menos oxigénio para a sobrevivência das bactérias e das células em geral. Este princípio da inflamação aplica-se a todos os animais. Existem alguns fatores específicos da espécie como diferentes receptores celulares, mas o conceito geral é o mesmo.

AP: O que pode desencadear a inflamação em animais de produção?

DW: A inflamação pode ser desencadeada por vários fatores de stress, especialmente agentes patogénicos e alguns eventos clássicos dependentes da idade têm um impacto negativo no estado de saúde do animal. O stress do desmame, por exemplo, é bem conhecido por desencadear a inflamação e por ter um impacto negativo na saúde intestinal. Outros exemplos são o parto ou a reunião de aniamis de diferentes lotes para engorda. Tudo o que tem impacto na função normal do tecido pode levar à inflamação e isto normalmente anda de mãos dadas com uma infecção, uma vez que a entrada de agentes patogénicos é facilitada.

AP: A inflamação está também relacionada com o uso de antibióticos?

DW: Definitivamente. O uso de antimicrobianos - dados por via oral ou parenteral - leva a uma deslocação da microbiota nas superfícies da mucosa, como o intestino. Especialmente após a retirada dos antibióticos, a mudança na microbiota pode então permitir a manifestação de bactérias indesejáveis, o que pode causar complicações que conduzem à inflamação.

AP: Que papel desempenha a inflamação subclínica nos animais de produção?

DW: Na inflamação subclínica, os cinco sinais cardeais de inflamação não são vistos em toda a sua extensão. O órgão afetado pode ser ligeiramente doloroso ou desconfortável, pode haver alguma perda de função, e há alguma infiltração com células imunitárias, mas não até ao ponto de uma inflamação aguda.

As consequências da inflamação subclínica são o crescimento e a eficiência alimentar dos animais jovens temporariamente prejudicados devido a processos inflamatórios em curso (por exemplo, causados pelo stress do desmame).

A mastite é um bom exemplo para mostrar a diferença entre os vários graus de inflamação. Com a mastite subclínica, o leite parece normal, mas é dada uma maior contagem de células somáticas. Talvez o úbere pareça um pouco inchado ou esteja ligeiramente mais quente ao toque.

Em contraste, se as vacas enfrentam uma infecção aguda do úbere, o carácter típico do leite desaparece e o úbere da vaca é muito doloroso e sensível.

AP: Quando é que vemos uma resposta imune exagerada?

DW: Em geral, as respostas imunes são reações bem orquestradas e bem afinadas, nem demasiado fracas nem demasiado fortes. Uma boa resposta imunitária funciona como uma orquestra. Só se todos os instrumentos estiverem no lugar certo, no momento certo, na quantidade certa, é que obtemos um som perfeito. Um exemplo em que esta orquestra afinada não funciona é a E. coli mastitis em vacas leiteiras. Aqui, os lipolissacarídeos da membrana da E. coli resultam numa reação exagerada do sistema imunitário: As células imunitárias no úbere estão constantemente a segregar os moduladores imunitários, o que, em vez de prevenir mais danos, na realidade aumenta os danos no tecido. Isto pode ser comparado ao condutor esquecendo-se de parar os tambores... e eles continuam a bater! Agora, se alguém tirar as baquetas, podemos recomeçar a tocar juntos em harmonia. Ou, no contexto da E. coli mastitis, se conseguir "amortecer" um pouco a resposta imunitária, dá ao sistema imunitário a oportunidade de trabalhar em conjunto de forma eficiente e de eliminar a infecção sem os efeitos secundários negativos de uma reação imunitária excessiva.

AP: Portanto, faz sentido pensar na gestão da inflamação?

DW: Sim! Em condições práticas, não é provável que a gestão, bem-estar, nutrição e pecuária possam ser sempre pontuais. Cada ferramenta - um novo celeiro, biossegurança melhorada, ou aditivos alimentares - que apoia o organismo a lidar com uma infecção mais rapidamente ou a gastar menos energia e nutrientes numa resposta é muito benéfica.

AP: Se contivermos a inflamação, podemos ter a certeza de que o corpo ainda é capaz de lidar de forma eficaz com uma infecção?

DW: Totalmente! Mais uma vez, o sistema imunitário nunca é desligado. É apenas controlado para que não reaja em demasia, mas seja capaz de reagir assim que for necessário.

AP: Uma palavra que é frequentemente mencionada em combinação com inflamação é "NF-κB". Consegue explicar o que é?

DW: NF-κB significa factor nuclear kappa - potenciador da cadeia leve de células B ativadas . É um dos principais fatores para ligar a transcrição de genes de citocinas pró-inflamatórias imunomoduladoras como a Interleucina 1 e o Factor de Necrose Tumoral. NF-κB é expressa em muitas células do corpo de todos os animais. Um pouco mais simplificado pode dizer-se que se for picado por alguém, a probabilidade de que as células picadas respondam com uma resposta inflamatória NF-κB é bastante elevada. O mesmo se aplica a todos os animais de produção".

AP: Qual é o seu conselho para os veterinários e tecnicos em termos de inflamação?

DW:Onde aplicável, otimize a gestão, nutrição e manejo, e evite o tratamento metafilático com antibióticos.

AP: Muito obrigado pelo seu tempo e ideias, Dirk!

Dirk Werling é professor de imunologia molecular no Royal Veterinary College, em Londres.

Dirk é doutor em virologia e possui um Ph.D. em imunologia. Após atuar como professor assistente no Instituto de Virologia da Universidade de Berna, Dirk foi para o Royal Veterinary College, em Londres, onde ocupa a cadeira de professor de Imunologia Molecular. Isso lhe dá a oportunidade única de desenvolver novas plataformas de vacinas para animais de produção, tendo como alvo a então (2007) recém-descoberta classe de receptores imunes inatos, como os receptores do tipo Toll.

Até o momento, esse trabalho resultou na apresentação de 3 pedidos de patentes diferentes e, junto com seu grupo de trabalho, Dirk possui mais de 100 publicações revisadas por pares, desde tópicos de pesquisa empírica, como a coevolução entre o hospedeiro e os patógenos, o reconhecimento de padrões específicos de espécies e a interação do microbioma e do sistema imunológico.

Póngase en contacto con nuestros expertos o envíenos un mensaje. Nos pondremos en contacto con usted lo antes posible.